In reaching conclusions about an individual's suitability for public office, Americans rarely account for the stupidity of a candidate's youth. And, to be honest, nor should they. Bush The Younger certainly put his own youthful stupidity in a fitting light by simply saying, "When I was young and irresponsible I was young and irresponsible." Though his near-abnormal incuriosity and notorious inarticulacy disqualified him in the eyes of many of us, observers and critics (okay, me included) must at least admire this ability, or rather willingness, to acknowledge bad behaviour. I suspect what irks people about the latest 'scandal' — I use the term with caution — is Romney's reluctance in confirming what the rest of us already know: that as a kid he was, frankly, kind of a jerk.

The 'news' this week on the Romney front came by way of the

Washington Post. Jason Horowitz's piece is troubling partly due to its vividness in description. "Friedemann followed them to a nearby room where they came upon Lauber, tackled him and pinned him to the ground," Horowitz writes. "As Lauber, his eyes filling with tears, screamed for help, Romney repeatedly clipped his hair with a pair of scissors." John Lauber, an unassuming, soft-spoken student one year behind the bully, was presumed to be gay, or 'queer' as they might have put it, by his classmates. The future presidential candidate considered Lauber's hair a little too long by the prestigious Cranbrook prep school's exacting standards, and thus adopted it as

his job to ensure it was cut. Lauber died in 2004, but was spotted by a witness to the incident at an airport in the mid-1990s, who apologized for not doing more to assist him. "It was horrible," the victim said simply, adding later, "It's something I've thought about a lot since then." A student who assisted in restraining the victim for Romney's hack-job haircutting enterprise was quoted by the

Post and recalled that the episode "happened very quickly, and to this day it troubles me." He, too, later apologized to Lauber. "What a senseless, stupid, idiotic thing to do."

Other accounts of various pranks are less disturbing, but worth remembering nonetheless. Leading a blind teacher into a closed door isn't exactly kosher, but still dwells rather comfortably on the 'prank' end of the spectrum. Though most of his classmates recall with fondness the (and here I make full use of the inverted commas) "pranks" he used to play, others remember a "sharp edge" to the young Willard Romney. Another student, who kept his homosexuality concealed but was at any rate the victim of abuse, was in the same English class as Romney, and remembers his contributions in class being punctuated by outbursts of "Atta girl!" from the presidential aspirant to-be. While anti-gay sentiment is rarely concealed within such environments, perhaps more surprising still is the gay student's recollection of various teachers using similarly-snide language. I don't think I'm pushing too many boundaries, or taking too many liberties with the term, when I say that this is gay bashing — the earlier mob haircut incident included.

What are we to make of these reports? I use the word

reports, not its cheap and easily-dismissed 'synonym'

allegations, because there is, quite simply, sufficient evidence to suggest that they are true. No one is out to allege that Romney was a rank schoolyard bully; we already

know that this was the case. The legitimate question, and the one we really ought to be asking one another, is whether or not these irksome stories mean anything in the context of a bid for the presidency.

Romney has said he cannot remember the attack on Lauber in particular, but that he apologizes for it anyway. May I just say: I think he's lying. But of course this I cannot prove, nor can I easily dismiss the notion, however, that an apology so long after the incident occurred, and so long after the death of the victim, means next to nothing. Politically, Romney is now desperately in need of a new genesis story. The one put forth by Horowitz in the

Post is so horribly unflattering I'm inclined to conclude that this, combined with the public's perception and general lack of enthusiasm for the candidate, make a campaign based on 'good character' — or something else equally intangible — impossible or worse. Why can't this man confront the story properly, and discuss his reckless actions with the seriousness the situation demands? Romney's inability to remember, and his empty apology, instead of taming the threat posed to his campaign by these revelations, makes the stories more troubling still.

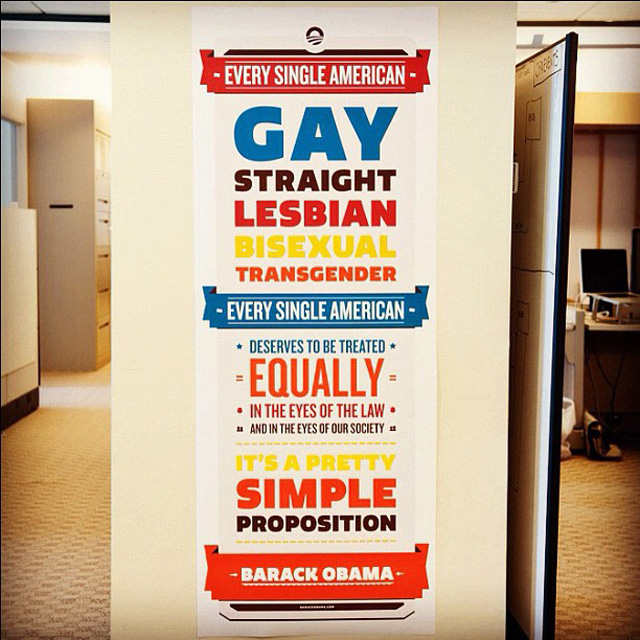

(Image: "Young Mitt Romney at Cranbrook, a prep school, where he is reported to have bullied another student." Courtesy of Cranbrook Prep School, via

Slate.)