No matter how many times I read these lines I’m stunned by their gutsiness, ferocity, and sheer verbal voltage. I recoil; I want to say, I didn’t say anything to you, D. H.! All I did was look at the damn book! Poets tend to beseech or cajole, seduce or flat-out ignore their readers; they don’t usually pick fights with them. Lawrence has got a lot of nerve.We've been reading Lawrence's poetry in my English class for a little while now. One couple worth noting is "The Oxford Voice". Do enjoy the way in which Lawrence takes every opportunity to mock his subjects, and what he sees as their ludicrous, affected intonation.

But all’s fair in love and war, and “Pomegranate,” at its core, is a poem about love. As Lawrence beats you into submission, it becomes clear that it’s over a lot more than a piece of fruit. Indeed, you’re getting it about the entire history of love in the West—and your own complicity in that sad story. If the authors of Genesis envisioned any one particular fruit dangling from that infamous tree in Eden, scholars argue it was likely the pomegranate. In the Greco-Roman tradition, those same ruby seeds cursed Persephone to an eternal half-life, consigned her to winter after winter with her abductor-husband, Hades, among the pomegranate groves of the dead. From Jerusalem to Athens to Rome, this is the fruit you get when love spoils into lust, when desire goes to seed. This is not a fruit you want to crack open.

A compendium of perspicacious reportage and a weblog about all things pertaining to politics, news and intergalactic agriculture; weblog of Alistair Murray.

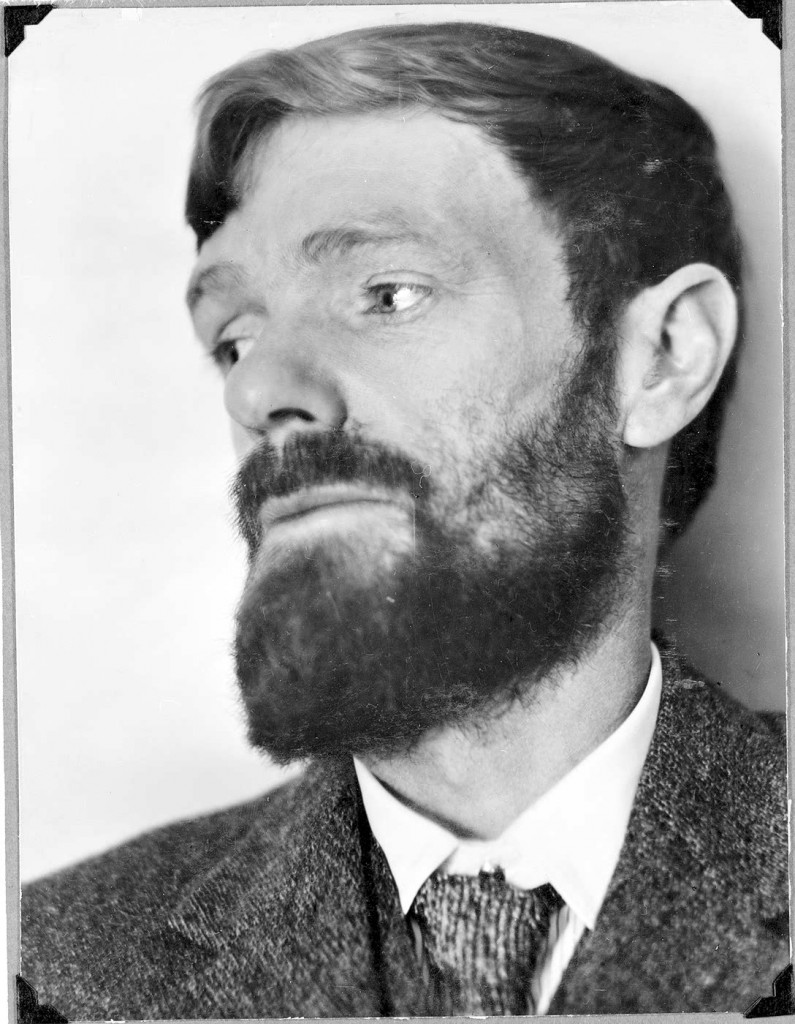

Poetic Ferocity

Upon reading D. H. Lawrence’s poem "Pomegranate" — which begins with the lines, "You tell me I am wrong / Who are you, who is anybody to tell me I am wrong? / I am not wrong" — Eli Mandel was rather struck by the poet's nerve: